From solid to pneumatic, from bikes to motor vehicles, wheels and tires are like so many other vehicle components: we take them for granted. Most of us are accustomed to the regular replacement of our car’s tires, which eventually wear out. It’s easy to forget (or ignore) how different it was just a few decades ago, before innovations like radial tires, long-life tread, run-flats, and TPMS (Tire Pressure Monitoring Systems). But what were tires like at the dawn of the automobile?

We are NOT going to make any attempt to document the invention of the wheel!

Whether made of stone, wood, metal, or some combination, the wheel has been around for many thousands of years. Our interest here is in the automobile’s use of rubber tires mounted onto a center disc.

Below are just the highlights of 100+ years of rubber tire innovations and improvements. It really begins with the bicycle, which went through several popular crazes in the 1800s. We will trace the path of tire development from bikes to cars, focusing on some of the better-known milestones in the industry.

BICYCLES BEGIN THE INNOVATION

VULCANIZED RUBBER

Horse-drawn carriages required strong wheels. As the pathways of the 19th century were hard earth, stone, or even unpaved fields, wood or metal wheels could stand up to these harsh conditions. The trade-off was an equally harsh ride. Rubber may have been considered as an alternative material, but in its natural state, it is sticky, gummy, and subject to temperature fluctuations, being soft in warm weather, and brittle in the cold.

Rubber’s usefulness changed for the better in 1839, when a man named Charles Goodyear (that last name may sound familiar) invented a process to vulcanize rubber. Vulcanizing rubber transforms it into a substance which is more durable, can be formed into a consistent shape, and can deform, or bend, and then return to its original shape. In other words, it was a significant improvement over the hard wheel.

PNEUMATIC TIRES

In the mid-1880s, Europeans began to develop the bicycle, and its popularity took off. Original bike wheels were wood, but sometime in the 1860s, solid rubber tires were introduced. Still, the rubber material, while long-lasting, did little to cushion the ride. (An early nickname for the bicycle was the “bone-shaker.”) And as the bicycle progressed, average speeds increased. The public wanted more comfort on this newest transportation fad. In 1888, a man named John Dunlop (another familiar surname), desiring his young son to have a more comfortable ride on his bike, invented the first practical pneumatic, or air-holding tire.

Coincidentally, the automobile industry was born around this same time.

DETACHABLE TIRES

These early tires were permanently mounted to their wheels. When a solid rubber tire wore out, the entire assembly was replaced. The bigger issue arose with pneumatic tires, as it was a difficult and time consuming process to make a repair. Although there are some claims for British inventors in 1890, the first effective, detachable pneumatic tire is usually credited to Edouard Michelin (our 3rd inventor with a recognizable name), who patented his version for bicycles in 1891.

HORSELESS CARRIAGES DRIVE THE DEMAND

TREADED TIRES

Rubber tires were originally smooth, as there was no inherent demand for a tread pattern (except for decorative or marketing purposes). As roadways improved and speeds increased, and as cars, unlike bikes, were used year-round in all kinds of weather, the need for better traction arose. In 1904, Continental Tire of Germany was the first to introduce a tread pattern on a tire. Grooved tires to help with traction in slippery conditions came about from the Goodyear Tire Company by 1908.

INNER TUBES

Early tires and wheels were made of materials which could not sufficiently contain air pressure. This, combined with inefficient mounting techniques and high tire pressures, resulted in a requirement that all tires use a rubber inner-tube, between wheel and tire, to hold the air.

BIAS PLY CONSTRUCTION

By the 1910s, tire engineering and manufacturing had evolved to use sheets of cotton cord material, cut at an angle (“on the bias”), layered, and molded into sheet rubber. So was born the “bias ply tire,” which remained the industry standard, at least in the U.S., until the 1960s.

RADIAL CONSTRUCTION

Like so many other tire technologies, the radial tire was initially developed early in the tire industry’s life, but a combination of poor design, lack of manufacturing know-how, and failure to find a market led to a lack of success. In 1948, the Michelin Tire Company produced the first commercially available steel-belted radial tire, so named because the tire’s cords were placed at a 90 degree angle (radially) to the wheel.

This Michelin X radial was used on a French Citroen, a car company which Michelin happened to own at the time.

BIAS BELTED CONSTRUCTION

Radial tires, for all practical purposes, were invented in Europe and became hugely popular there. Radials promised longer life, better handling, and improved fuel economy. Other tire companies in Europe and Japan began to manufacture them, and by extension, car companies on those continents adopted the tire. But in the U.S., there was resistance as American tire companies were hesitant to invest in expensive equipment to make the changeover.

American car companies, thinking that they would need to re-engineer their suspension systems, rejected the radial tire as “too harsh” for their vehicles.

Goodyear aimed for a compromise. In 1967, they brought to market a bias belted tire, which was a bias-ply tire with an additional fiberglass belt. It had longer tread life than a bias-ply and could be used on soft American car suspensions. But a radial tire it was not. When the first gas crisis hit in 1973, Americans began to buy more fuel-efficient, radial equipped imports, and demanded better mileage from their own cars. The radial tire eventually found its way onto all American-built cars by the early 1980s.

TUBELESS TIRES

Tube-type tires were around for more than half of the 20th century. Early attempts to improve tire/wheel sealing and eliminate tubes were unsuccessful. The B.F. Goodrich Tire Company filed for a patent for a “pneumatic tire without inner tube” in 1946, which wasn’t granted until 1952. The first U.S. car to use tubeless tires was the 1954 Packard Clipper.

RUN FLATS

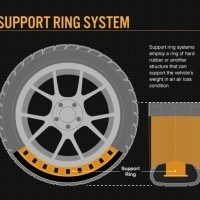

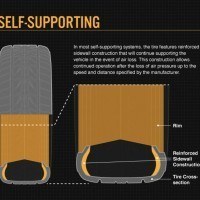

Because of poorly-surfaced roads, flat tires were a very common problem for those brave early “automobilists.” It took a long time for the U.S. to provide for widespread and improved roads. (The U.S. Interstate Highway System didn’t begin until 1956.) Cars typically carried more than one spare. If the driver could not fix the flat him/herself, a repair station might be many miles away. The Dunlop Tire Company, during the 1970s-1980s, made the first large-scale, commercially successful “fail-safe” wheel/tire combo, eventually making it standard on certain British car models.

Even in modern times, a flat-tire becomes a time-wasting inconvenience at best, and a deadly highway hazard at worst. The concept of a tire which, although punctured, can be driven on for short distances continues to be attractive, although higher cost is a detriment. Some automakers have turned to run-flats not only for safety, but as a way to eliminate the spare tire, saving weight, trunk space, and of course, cost.

THE 21ST CENTURY

Tire Pressure Monitoring Systems, or TPMS, are required as standard equipment on all new cars sold in the U.S. This system provides an additional layer of safety by giving early warning to a driver should tire pressure fall too low. Tire companies, starting with run-flats and moving to TPMS, have begun to further come up with ways to completely eliminate the issue of low or no pressure.

Making the rounds on the Internet over the last few years is the concept of the airless tire, also known as the NPT, or non-pneumatic tire. Modern plastics combined with modern manufacturing technologies has resulted in a one-piece plastic wheel/tire (sometimes called a tweel), strong enough to support a car’s weight yet resistant to deflection at highway speeds. There are still plenty of downsides: they are heavier, have high rolling resistance, and don’t dissipate heat well. This has not stopped Michelin and Bridgestone, among others, from continuing development.

As we continue to move toward the eventuality of the autonomous car, what does this mean for the modern tire? If the occupants are no longer driving, they will likely be even less interested in changing a flat, so expect to see run-flats increase above their present 3% of the market. However, tires as we know them are not going anywhere just yet and new tread technologies will likely mean incremental improvements.

In the meantime, we are in the fortunate position of being able to purchase tires which are state-of-the-art, giving us performance, comfort, and safety that the early Goodyear, Dunlop, and Michelin could never have imagined!

*Richard Reina is a Product Trainer at CARiD.com and lifelong automotive enthusiast.

http://www.automoblog.net/2016/02/17/history-of-tires/

No comments:

Post a Comment